Dance Touring and Embodied Data

Some Approaches to Katherine Dunham’s Movement on the Move

Abstract

How dance circulates transnationally is an important question for dance studies right now, and we ask how digital methods can extend this inquiry. This article represents the first stage of a larger research project that considers the kinds of questions and problems that make the analysis and visualization of data meaningful for the study of dance in a historical context. We pursue this work through the exemplary case study of Katherine Dunham and her global legacy. A prolific twentieth century dance artist, Dunham choreographed and performed in operas, nightclubs, Broadway shows, Hollywood films, and modern concert dance. Over a career that spanned eighty years, Dunham worked across five continents in many contexts, from her early anthropological research in Haiti to her curatorial, pedagogical, activist, and administrative projects later in Dakar, New York, and East St. Louis. Dancers around the world today continue to cite her as an influence and inspiration.1

In this short piece, we focus specifically on a dataset we manually curated to document Dunham’s location nearly every day for the four years between January 1st, 1950 and December 31st, 1953. As part of a critical mixed methods approach, this dataset helps us to think about embodied, transnational labor in Dunham’s everyday practices of making-do as an African American female artist in the mid-twentieth century. First, we describe the curation of the dataset itself. Then, we turn to two points of entry that digital visualization and data analysis provide: patterns of travel that correlate with financial support, and the corporeal wear and tear produced by what we have elsewhere called “movement on the move.”2 In this essay—and in our Dunham’s Data research as a whole—we follow imperatives to bring embodiment in digital research in a literal way, seeking to use our training as dance scholars in order to access the lived, bodily experiences that both underpin and haunt such data.3

We manually assembled the bulk of this dataset from Dunham’s personal and professional correspondence, contracts, receipt books, personal logs, programs, and newspaper clippings. Although Dunham was a rigorous self-archivist, no single document reliably indicates where she was at a given moment, and we routinely cross-reference and reconcile multiple data points to achieve as attentive and precise an itinerary as possible. Because she travelled so much, her correspondence was often sent or received “in care of” and postcards from one town were postmarked in another city. Similarly, advertisements and previews in newspapers give a limited view of her stays since her contracts lengthened or shortened in relation to the financial success of her shows. We supplemented Dunham’s archives with additional documents, including immigration records, local newspapers, and historical transit maps and schedules. For the four-year period 1950–53, we have identified with a reasonable level of confidence the cities and countries where Dunham began and ended 93% of her days—1359 out of 1461 days. We are currently expanding this dataset to cover over thirty years of her performing career.

What constitutes data is already an interpretation that is further processed through acts of collection and display—an idea that Johanna Drucker has described as “capta” to acknowledge “the situated, partial, and constitutive character of knowledge production.”4 For example, we arrived at the four-year itinerary through a process of inference and deduction that also negotiated more fuzzy meanings. When such datasets power visualizations to give us greater purchase on Dunham’s touring and performance schedule as a whole, the point is not to create something that might appear to be “natural representations of pre-existing fact,” but to lead with dance-based and humanistic values.5 For us, this means substantiating bodily experience and making the work of performance visible—from time spent in rehearsal to the labor of travel. This is a critical reminder for all data, and especially for that which seeks to represent black embodiment and experiences while resisting the “devastating thingification of black women, children, and men” that is entangled with histories of quantification from the slave trade onwards.6

A precise cataloguing of travel is particularly important for a choreographer whose artistic practice is uniquely informed by real and imagined engagements with geographic locations—what has been called Dunham’s “diasporic imagination.”7 Although scholars have tracked Dunham’s extensive travels on an ad hoc basis, Dunham’s Data represents the first attempt to build a comprehensive dataset of her whereabouts, a project that can not only serve as a reference but also spur further scholarship. We initially began to build this dataset to understand the relationship between Dunham’s choreographic and ethnographic work by analyzing the ways her dances both drew on place and circulated these images, movements, and sounds to other places—a set of questions that we are still pursuing. In the process, however, we realized how much information was already contained in this reference dataset, which demanded a kind of everyday analytic to grapple with the way a granular view, in turn, lends itself to understanding the politics of lived experience. In a longer essay, we articulate this “politics of the everyday” in terms of Katherine McKittrick’s theorization of the stakes of making visible the ways in which black women’s geographies of the everyday are lived.8 As dance scholars, we are also interested in the implications of such a scalable analytic for dance history.

Above is a video flythrough of this dataset plotted in a space-time aquarium using ArcGIS that allows us to show the geographic dimensions of where Dunham traveled over the course of four years while retaining the sequence of her visits. Each day for which we have location data is represented by a dot, although these become compressed when viewing the map at a distance. Looking day by day foregrounds the amount of work and travel Dunham is doing—both with and without her company—and the physical and emotional toll that such work implies. It produces a visceral effect to look at a map like this with the knowledge that Dunham is performing or rehearsing for at least 72% of the days in this four-year period, not counting the professional networking, writing, or researching local dance cultures that were also part of her overall workload.

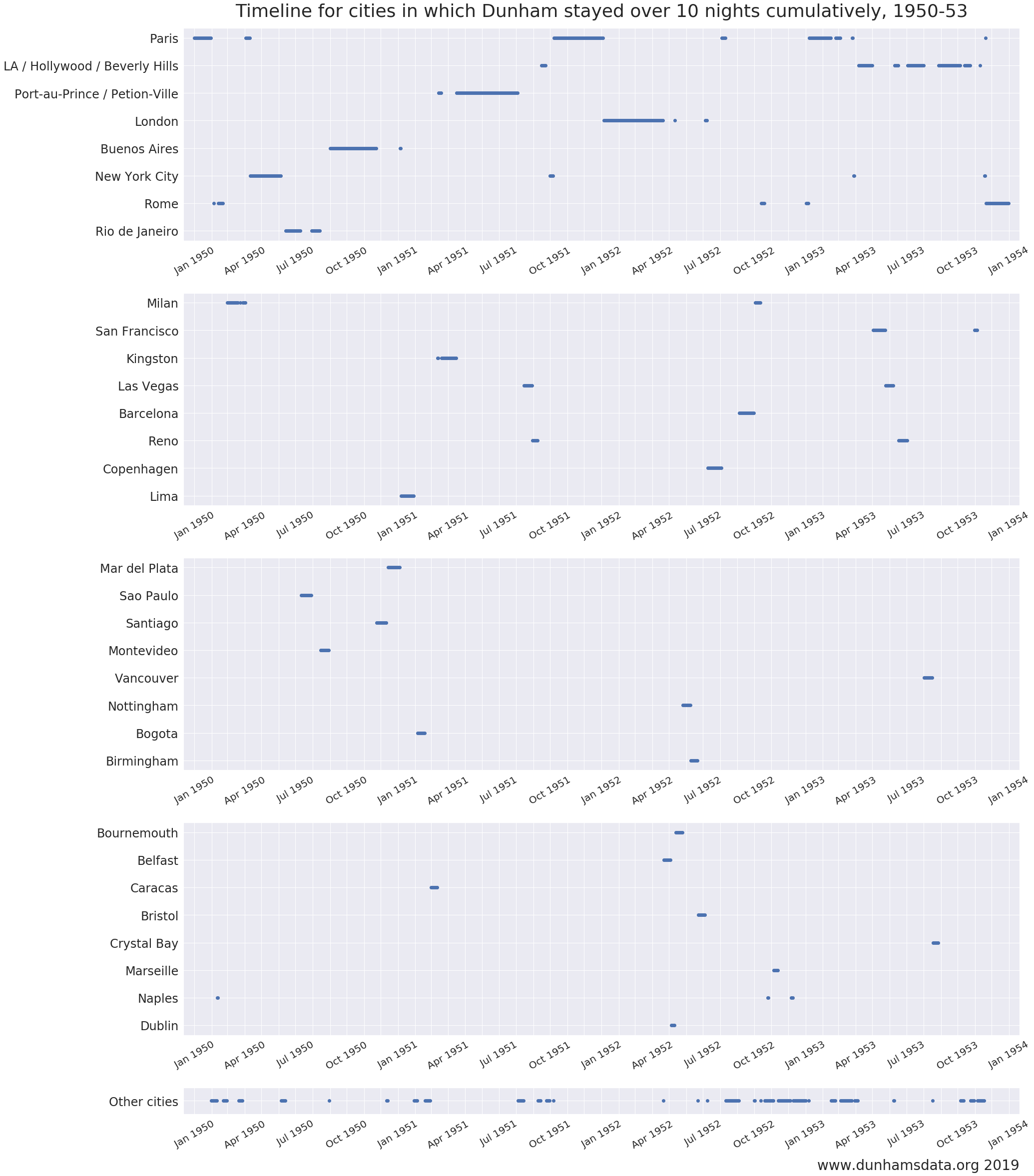

This space-time aquarium clearly shows the places where Dunham had lengthy stays and the places to which she returned.9 Because Dunham had no lasting public or private sponsorship, her touring pathways and the duration of her stays offer insight into solvency and the overall support available to sustain her ongoing work. As a result, locations become meaningful, with those where she lingered signifying financial success (or sometimes layoff periods as well). Returning to a place may further indicate expectations of repeat successes or point to investments of an affective rather than financial variety, as we see, for example, with Haiti. There is a tension here in the idea of support; at the same time that constant travel demonstrates an international interest in and audience for Dunham’s work, it is also a difficult means of artistic survival. Figure 2 visualizes Dunham’s stays and returns with a timeline that enables us to examine shifting sites of support in terms of their change over time. It facilitates comparisons across cities by compressing a large span of time and global travel into a visually comprehensible chart.

Looking at figures 1 and 2, we see that Dunham’s patterns of travel change over these four years. Scholarship on Dunham tends to focus on several key cities, three of which appear in the top cities of figure 2 (Paris, Port-au-Prince, and New York City). However, this dataset allows us to trace the many other cities that comprise Dunham’s international circulation, and to observe her increasing precarity as stay-lengths shorten from late 1952 to mid-1953. We also see the proportion of nightclub work on the West Coast of the United States, the significance of which Dunham scholarship has not yet addressed. During this period, Dunham visited the Los Angeles area six times for a cumulative total of 119 days. (In fact, the only place where Dunham spent more time overall than Los Angeles was Paris—180 days over seven visits). She spent almost that number of days again in other parts of the western US and Canada, including Las Vegas, Reno, San Francisco, Crystal Bay, and Vancouver. Analyzing the geographic distributions of financial and affective support in terms of her stays and returns, we are able to better assess changes in Dunham’s patterns of travel and what they prompt for further inquiry—from examining cities that have previously been overlooked but which supported Dunham’s global reach, to the politics that are surfaced in her daily practices of making do. The substantial amount of nightclub work further illuminates a lacuna in dance history, which has tended to overlook the importance of non-concert venues; this is something we seek to address.

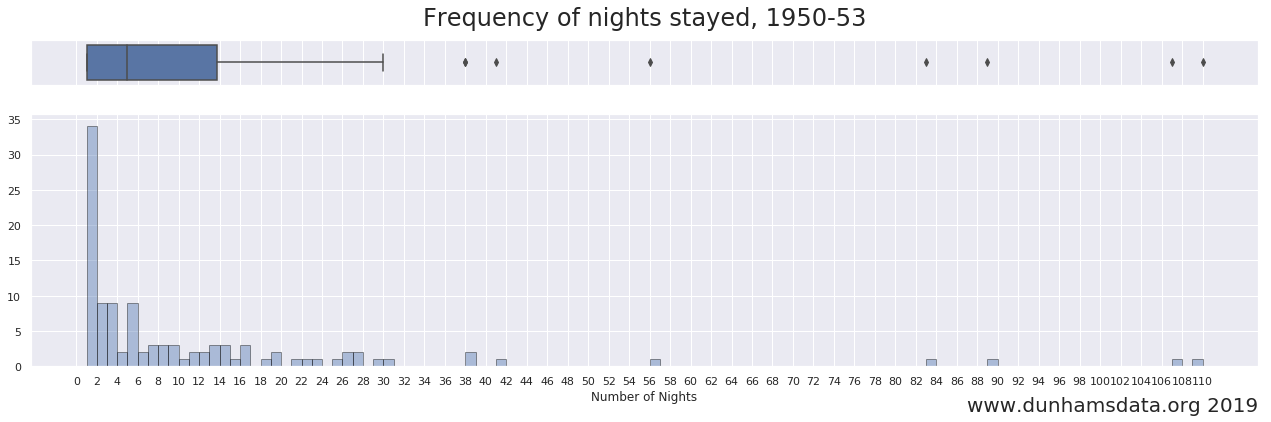

Visualizations such as these can obscure the labor of performing bodies traveling between cities and performing in them. Yet, exploring these patterns as they emerge day by day not only reveals some of the strategies that Dunham used to adapt and keep going, but also gestures to the wear and tear of being on the road. We have already mentioned time spent in rehearsal and performance, but travel itself imposes further stressors. Across the 1359 days that we tracked, we have identified 110 distinct trips. A statistical analysis of stay distribution reveals a median duration of five nights (Figure 3), with most stays lasting between one day and two weeks. In other words, we are talking about almost constant travel, and this four-year period is not an anomaly. It is, rather, the pattern we are beginning to discover across many decades of Dunham’s career. This has enormous implications for considering wellbeing as embodied experience in relation to crafting a transnational life in performance.10

The dataset and three visualizations depicted in this short essay engage with dance both as a mode of thinking about archives of moving bodies, and as an object of historical study. Dunham scholars already understand the mid-1930s to late-1960s to be one of extensive international travel for Dunham, but our expanding dataset is beginning to show the punishing pace of her touring and indicate the presence and absence of sustaining support structures. We are currently in the final stages of building out this daily itinerary to encompass 1947–60, with the goal of ultimately representing the full thirty-year period. The daily itinerary dataset stands at the core of a host of further inquiries on which we are embarking, from the relationship between choreography and ethnography in Dunham’s work, to the trajectories of the hundreds of performers who traveled alongside her.11 This labor-intensive work already seeds a foundational argument for the combination of dance history and digital methods: that any kind of transnational analysis in dance requires a granular understanding of travel and lived experience at the scale of the everyday that makes visible when, where, and what we mean when we say “transnational.” Even with our critical mixed methods approach, however, the data does not stand on its own; rather, we must constantly return to “flesh out” this data by considering it alongside the archival artifacts and lived histories from which it was derived. As we continue these explorations, we also push further into the difficulty of rendering fleshy, bodily experience through graphical representation.12 Amplifying the materiality of bodies in and through digital representations is what is at stake in bringing dance history and digital humanities into deeper conversation.

Bibliography

Bench, Harmony and Kate Elswit. “Mapping Movement on the Move: Dance Touring and Digital Methods.” Theatre Journal 68, no. 4 (2016): 575–96. https://doi.org/10.1353/tj.2016.0107.

Bench, Harmony and Kate Elswit. “‘Checking In’: The Flows of Dunham’s Performers.” Dunham’s Data Research Blog. (March 28, 2019). https://www.dunhamsdata.org/blog/checking-in-the-flows-of-dunhams-performers.

Bench, Harmony and Kate Elswit. “Katherine Dunham’s Global Method and the Embodied Politics of Dance’s Everyday.” Unpublished article, last modified July 31 2019.

Clark, VèVè. “Performing the Memory of Difference in Afro-Caribbean Dance: Katherine Dunham’s Choreography, 1938–87.” In History and Memory in African-American Culture, edited by Geneviève Fabre and Robert G. O’Meally, 188–204. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Clark, Vèvè A., and Sarah East Johnson, eds. Kaiso! Writings By and About Katherine Dunham. Studies in Dance History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005.

D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Lauren Klein. Data Feminism. Cambridge: MIT Press, forthcoming.

Drucker, Joanna. “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 5, no. 1 (2011). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/1/000091/000091.html.

Gigliotti, Simone, Marc J. Masurovsky, and Erik Steiner. “From the Camp to the Road: Representing the Evacuations from Auschwitz, January 1945.” In Geographies of the Holocaust, edited by Anne Kelly Knowles, Tim Cole, and Alberto Giordano. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014.

Jimènez Mavillard, Antonio. “First Things First: Days and Nights.” Dunham’s Data Research Blog. (August 1, 2019). https://www.dunhamsdata.org/blog/first-thing-first-days-and-nights.

Johnson, Jessica Marie. “Markup Bodies.” Social Text 36, no. 4 (2018): 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-7145658.

McKittrick, Katherine. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Notes

Dunham’s Data is supported by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council, Research Grant AH/R012989/1. Writing and datasets are equally co-authored by Kate Elswit and Harmony Bench; name order is alphabetical.

-

See, for example, Clark and Johnson, Kaiso!. ↩

-

Bench and Elswit, “Mapping Movement on the Move.” ↩

-

See D’Ignazio and Klein, Data Feminism. ↩

-

Drucker, “Humanities Approaches,” paragraph 3. ↩

-

Drucker, “Humanities Approaches,” paragraph 3. ↩

-

Johnson, “Markup Bodies,” 58. ↩

-

Clark, “Performing the Memory of Difference.” ↩

-

McKittrick, Demonic Grounds, 21; Bench and Elswit, “Katherine Dunham’s Global Method.” ↩

-

On stays, see Jimènez Mavillard, “First Things First.” ↩

-

Bench and Elswit, “Katherine Dunham’s Global Method.” ↩

-

Bench and Elswit, “‘Checking In’.” ↩

-

See Gigliotti, Masurovsky, and Steiner, “From the Camp to the Road”; Bench and Elswit, “Katherine Dunham’s Global Method.” ↩

Authors

Harmony Bench,

Department of Dance, Ohio State University, bench.9@osu.edu,  0000-0002-0550-8124;

Kate Elswit,

Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London, Kate.Elswit@cssd.ac.uk,

0000-0002-0550-8124;

Kate Elswit,

Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London, Kate.Elswit@cssd.ac.uk,  0000-0001-9541-107X

0000-0001-9541-107X